Reliability and Efficiency in Process Heaters

- Posted by: Euler Jimenez

- Category: Heat transfer

The importance of human factor on process heater’s reliability.

Process furnaces are essential equipment in a refinery. They consume very high volumes of fossil fuels with proportional amounts of CO2 emissions to the atmosphere. They are highly expensive equipment that operate with flames at very high temperatures and their failures can be critical to the economy of the refinery. When it comes to natural draft heaters, which make up a high proportion in refineries it is, unfortunately, not possible to automate their entire operation since they are not 100% airtight equipment such as a heat exchanger or they do not work with positive pressure such as water-tube steam generators. This lack of airtightness, which implies being “open to the atmosphere”, places the ultimate or definitive responsibility of the heater thermal efficiency and the preservation of its mechanical integrity on the shoulders of control room and field operators (i.e., the human-heater interface).

Simply put, the operational reliability of heaters depends largely on the knowledge and skills of fired heater operators.

Determinant operational variables

For the combustion reaction to occur, the heater (if it is well-maintained) draws in ambient air through its burners based on two basic operational parameters: draft and excess, both oxygen measured at the top of the radiant section (or bridgewall). These two variables must be simultaneously regulated by two mechanical devices: a) the burner air registers and b) the stack damper. These two devices, however, will be operated as determined by the criteria of the two aforementioned operators.

Various alternatives of control systems have been proposed to automate the operation of heaters based on draft and excess oxygen levels. However, most of these systems have run into the same obstacle: the difficulty of achieving airtightness in equipment as large and as hot as process heaters due to air infiltrations into the heater through the slits between casing plates, unfit seals of observation windows, annular gaps through which the coil tubes enter and exit the heater, and so on. This “parasitic” air, which does not participates in the combustion reaction, alters excess oxygen measurements rendering heater control pointless.

When dealing with not very old heaters (i.e., less than 30 or 25 years) the control room operator must manually (albeit remotely) control the opening of the stack damper while the heater field operator must maintain radio communication with his colleague to manually regulate the burner air registers with the same purpose, that is, to maintain the draft and excess oxygen, that is, the Air/Fuel ratio within the operational goals defined by heater design guidelines.

What usually happens with refinery process heaters?

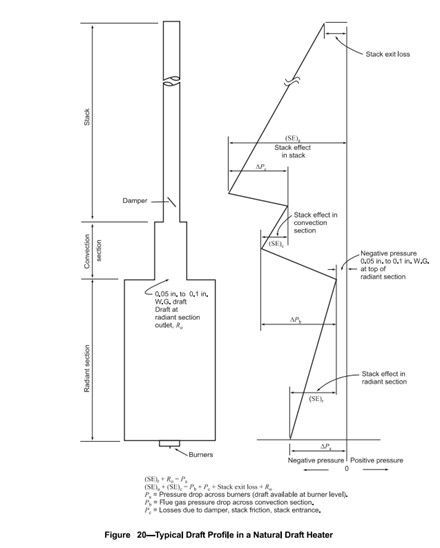

The API RP 535 standard defines in Figure 20 (pp. 55) the typical draft profile in natural draft heaters.

A “de facto” definition

Operators, either trying to “protect” the furnace from a deficient air condition, due to lack of understanding of technical fundamentals or due to lack of adequate supervision, define a “de facto” operational condition for heater draft and excess air. This definition implies operating the furnace with high levels of draft (< -0.15 “H2O) and excess oxygen (> 4.0% wet basis). This mode, nonetheless, can be described as “energy wasteful “.

But, in addition, the damage caused by an operation far from conditions recommended by heater designers is not only reflected in higher CO2 emissions to the environment. It also affects the mechanical integrity of the equipment. For example, high excess air levels caused by high draft (or more negative draft) bring with them higher fuel pressures to compensate for the heat lost by overheating the air. These higher pressures alter the characteristics of the flames causing them to impinge directly on the tubes of the radiant section causing localized coking of the “charge” within the tubes. They also cause higher temperatures in the convective section, which can cause deterioration of the extended surfaces (i.d., fins) of the tubes in this section.

Risky operation

Operators tend to prefer operation with excess of air because, doing the opposite, which is, operating with deficient air could have catastrophic (and immediate) results to the heater. In a very low draft condition (> -0.05 “H2O), the air intake through the burners would be limited and could be insufficient to complete the combustion of all the fuel. If unburned fuel accumulates inside the furnace, it will begin to suffocate and any possible untimely entry of air would cause an explosion, generally with extensive damage to equipment, losses in production and eventually with possible severe effects on personnel.

Operating in conditions away from design specifications is mechanically damaging to the furnace and environmentally damaging to the refinery. The de facto definition of draft and excess oxygen should be overcome based on training and a thorough understanding of the process by heater operators and supervisors. It would also be convenient to add economic incentives for the operators depending on the fulfillment of the operational goals set to obtain the maximum possible thermal efficiency.

If you want to know more:

WhatsApp

WhatsApp