Continuous Operational Tune-up (COT) of Fired Heaters

- Posted by: Euler Jimenez

- Category: Heat transfer

Continuous Operational Tune-up (COT) of process furnaces is the fastest and cheapest option to mitigate CO2 emissions in oil refineries.

CO2 emissions in petroleum refineries

Process heaters in petroleum refineries consume large volumes of fossil fuels and emit proportional amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. Most of these heaters have a natural draft design and operate “open to the atmosphere”, but at a slightly lower pressure than atmospheric pressure to ensure the combustion air supply and to guarantee the confinement of hot gases inside the equipment. This lack of airtightness in the heater makes it impossible to fully automate its operation and imposes on operators (i.e., the human-furnace interface) the ultimate and definitive responsibility for fuel consumption, CO2 emissions, and the preservation of its mechanical integrity.

Day-to-day heater control

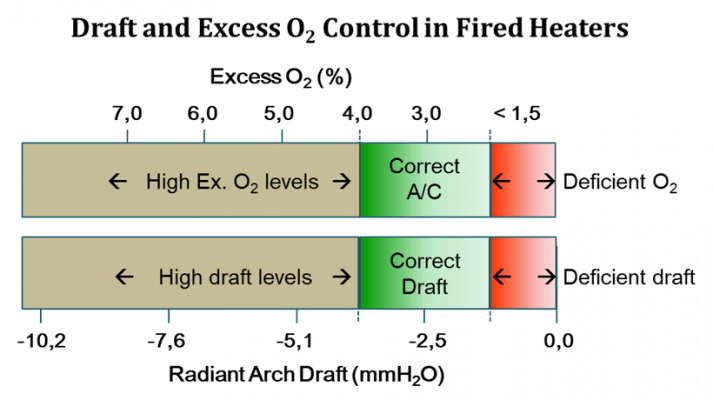

The combustion reaction in a heater requires ambient air that enters through the burners as a function of draft and an excess of oxygen. In natural draft heaters, console and field operators should coordinate their efforts to control the manual stack damper opening (remotely) and the register openings (always manually) to maintain draft and excess air levels within previously established optimum operational goals.

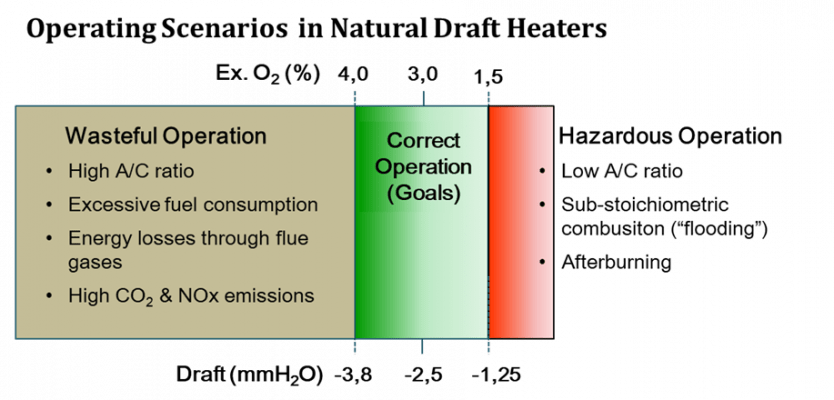

The diagram below shows the operational scenarios faced by process furnace operators and the options they have to control them.

“De facto” definition of heater draft and excess air

Operators often define a “de facto” operational condition for the draft and excess air as a way to avoid a deficient air condition. Usually, this artificial definition implies the operation of the furnace with high draft (< -3.8 mmH2O) and excess oxygen (> 4.0% wet base) levels, which configures a wasteful operational mode in terms of energy consumption and obviously a harmful condition for the preservation of equipment mechanical integrity.

Draft and excess air deficiency

On the other hand, An operation with an air defect could have immediate and catastrophic results for the heater. Exceeding the draft conditions to very low levels (> -1.3 mmH2O) would result in an insufficient air intake, thus limiting the combustion reaction and increasing the probability of flame failures (“flameout”). The accumulation of unburned fuel inside the furnace can result in the complete suffocation of the equipment, before which any possible untimely entry of air could cause an explosion, causing damage to the equipment, loss of production, and eventually injuries to the personnel.

Correct operation

The correct operation of the heater is based on the design specifications: draft usually -2.5 mmH2O (-0.10 “H2O) and excess oxygen 3.0%. These defined parameters are essentially guidelines. In practice, the operator has some room for maneuver, perhaps less efficient from a thermal perspective but still operationally safe. This safety margin is usually defined as -1.3 mmH2O (0.05 “H2O) for draft and about 1.5% for excess air.

The following diagram summarizes the three operating scenarios of a natural draft process furnace.

Key elements of a Continuous Operational Tune-up (COT) program

A program of this nature should have competent operators and proactive engineers and supervisors. Employees should be stimulated and motivated in different ways and supported by management levels.

The EOC program would be aimed at operators and supervisors and its basic objective would be to keep the furnaces operating within the draft and excess oxygen operational goals set for each unit. Inasmuch as diverse economic, political, and social reasons that are entirely understandable, the closure of oil refineries is not part of the immediate plans and strategies to comply with the Paris or Glasgow agreements. It is therefore unavoidable to begin minimizing the emissions produced by the burning of fossil fuels through exhaustive and continuous attention and control programs on the main sources of these emissions: process furnaces.

Since both the rational use of fuel and the maximum containment of emitted pollutants ultimately depend on operators, the simplest option, with the lowest cost and a high socioeconomic content, lies in comprehensive technical training and economic stimulus for them. Making this decision should be an inescapable corporate responsibility and a commitment that should be assumed by refinery management levels.

If you want to know more:

WhatsApp

WhatsApp